The most common question I ask myself when looking at my indoor garden in January is, “Can I really take those leaves, or will I regret it?” You’re making a soup or a pasta dish, and you spot that pot of basil or parsley sitting on the windowsill. It looks alive, but it’s definitely not booming like it was in July. The temptation to snip a bunch of stems is strong, but there is a nagging fear that cutting it now might be the final straw for a plant already struggling with the shorter days.

The short answer is yes, you can harvest herbs in winter, but you have to change the way you do it. You cannot harvest with the same aggressive energy you used in the summer.

In my experience, winter harvesting is more of a negotiation with the plant than a routine. It’s about taking a little bit here and there without pushing the plant into shock. There are some herbs that will happily give you fresh leaves all winter, and there are others—like my dramatic basil—that might need a complete vacation until spring.

I’m Wissam Saddique. I got into indoor container herb gardening after trying to keep a few basic herbs alive in a small apartment and realizing how little straightforward information existed for people working with limited space. What started as a simple attempt to grow basil on a windowsill gradually became a more deliberate process of testing different containers and observing how plants react to indoor life.

I’ve spent the last few winters carefully watching my herbs to see exactly how much I can get away with. I’ve learned that keeping fresh flavors on your plate in January is possible, but it requires patience and a much lighter touch.

The Energy Budget: Why Winter Plants Are Different

To understand whether you should harvest, you have to understand what your plant is going through right now. I like to think of plants as having a bank account of energy.

In the summer, the days are long and the sun is intense. The plant is making “money” (energy from photosynthesis) faster than it can spend it. When you cut off a branch in July, the plant has plenty of surplus cash in the bank to immediately grow a new one. It barely notices the loss.

Winter is different. Even inside a warm apartment, plants know it is winter. The light coming through the window is weaker and lasts for fewer hours. The plant is operating on a very tight budget. It is making just enough energy to keep its existing leaves alive and maybe grow a tiny bit.

If you come along and chop off 30% of its leaves, you aren’t just taking the harvest; you are taking away the solar panels it uses to generate that scarce energy. If you take too many, the plant goes into debt. It starts dropping lower leaves, turns yellow, or just stops growing entirely because it doesn’t have the resources to heal the wound and regrow.

So, before I reach for the scissors, I always look at the plant and ask: “Can this plant afford to lose these leaves right now?”

Knowing Which Herbs Can Handle the Cut

Not all herbs have the same winter budget. Through my trials in my apartment, I’ve realized that herbs fall into three distinct categories during the colder months. Knowing which category your plant belongs to is half the battle.

Some plants are surprisingly tough and will keep chugging along, while others will punish you for even looking at them the wrong way in December.

The Winter Warriors (Harvest with Caution)

These are the plants that seem to tolerate my apartment’s winter conditions the best. They don’t grow fast, but they don’t usually die back just because I snipped a few sprigs.

- Parsley: This is my reliable winter friend. It grows slowly, but it rarely complains about a weekly snip.

- Mint: As long as it isn’t right next to a drafty window, mint usually keeps pushing out new growth, though the leaves might be smaller.

- Chives: They slow down significantly, but you can usually take a few blades here and there without killing the clump.

The Woody Survivors (Harvest Very Lightly)

Herbs with woody stems are generally hardy, but they are very slow to recover in winter. Because they grow so slowly, any cut you make is going to be visible for months.

- Rosemary: It stays green, but it is barely growing. I only take tiny tips.

- Thyme: Similar to rosemary. It holds its ground, but if you cut it back hard, it might look like a stick figure until March.

- Oregano: It often goes semi-dormant. It’s alive, but it’s napping.

The Sensitive Souls (Let Them Rest)

These are the plants that give me the most trouble in my apartment during winter.

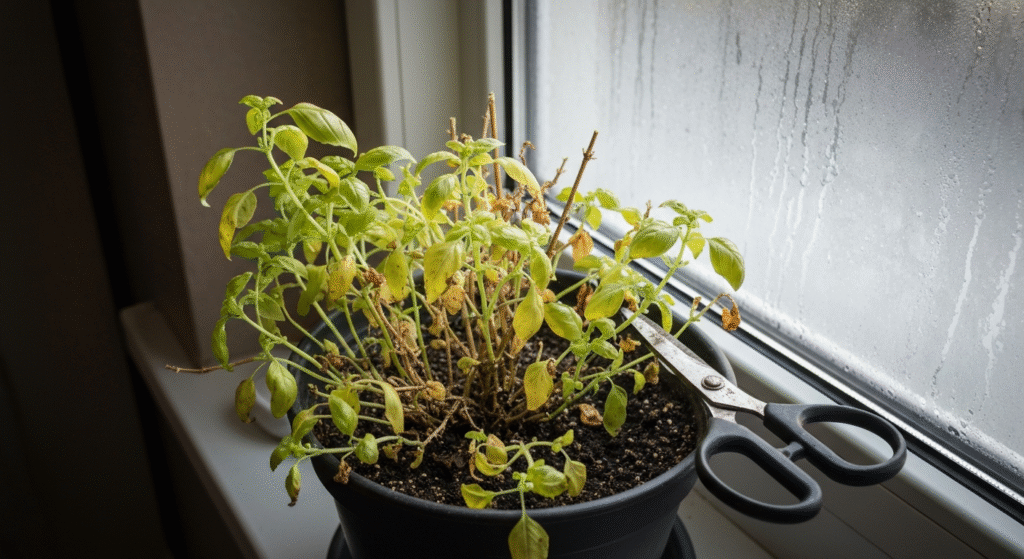

- Basil: This is the big one. Basil loves heat and intense light. In winter, it is often just trying to survive.

- Cilantro: It tends to get leggy and weak quickly if the light drops too much.

- Dill: It often stretches out and becomes floppy.

Here is a breakdown of how I adjust my expectations based on the herb type.

Note: This table is based on my personal observations growing in a standard apartment setting without industrial setups. Your results might vary slightly depending on your specific window direction.

| Herb Type | Summer Harvest Habit | My Winter Adjustment | Risk Level |

| Basil | Heavy pruning weekly | Rest completely or 1-2 leaves only | High |

| Parsley | Cut bunches weekly | Snip outer stems every 10 days | Low |

| Mint | Cut back aggressively | Harvest tips only, every 2 weeks | Low |

| Rosemary | Harvest sprigs often | Take 1 inch off the top only | Medium |

| Thyme | Cut bunches | Snip side shoots sparingly | Medium |

The “December Pesto Mistake”

I want to share a specific failure so you don’t have to repeat it. A couple of years ago, I had a beautiful basil plant that had survived into December. It was smaller than its summer self, but it was green and leafy. I decided I wanted fresh pesto for a holiday dinner.

I harvested about 50% of the plant. In my mind, I thought, “It’ll grow back.” It did not grow back.

Within three days, the remaining leaves turned pale yellow. The stems started to shrivel. The plant had been using every bit of energy just to maintain those leaves. When I took half of them, I bankrupted the plant. It didn’t have enough energy left to photosynthesize and recover. I ended up losing the whole thing before New Year’s.

The lesson I learned: In winter, herbs are for garnishes, not for main courses. If you need a cup of basil for pesto, buy it at the store. If you need three leaves to top a pasta dish, cut them from your plant.

Adjusting the “One-Third” Rule

If you have read any gardening books, you have probably heard the “One-Third Rule.” This rule states that you should never harvest more than one-third of the plant at a time.

In winter, you need to throw that rule out the window. It is far too aggressive for indoor plants in low light.

For my indoor garden, I use a 10% Rule during winter. I never take more than 10% of the plant’s total foliage at one time.

Why smaller cuts matter

When you take a massive cut, the plant has to redirect all its resources to healing that large wound and stimulating dormant buds to grow. In winter, those resources are scarce. By taking only a leaf here and a sprig there (the 10% rule), the plant doesn’t register the loss as a major trauma. It can easily fill that small gap without exhausting its energy reserves.

This means I am harvesting much less food. I accept that. I would rather have a small sprinkle of fresh thyme on my potatoes every week all winter long than have one big harvest in December and a dead plant in January.

Signs Your Herb Needs a Total Break

Sometimes, even the 10% rule is too much. There are times when I look at my plants and decide to put the scissors away completely for a month or two. You have to learn to read the plant’s body language.

If you see these signs, stop harvesting immediately. Let the plant rest until you see vigorous new growth in the spring.

1. The “Stall”

This is the most common sign. You cut a stem of mint, and two weeks later, the plant looks exactly the same. No new leaves have popped out. The cut stem hasn’t produced side shoots. This means the plant is dormant or just maintaining. If it isn’t growing, don’t cut it.

2. Pale New Growth

If your rosemary pushes out new needles but they are a very pale, sickly green or yellow compared to the older growth, the plant is struggling for light. It is stretching its resources too thin. Harvesting now will just stress it further.

3. Leaf Drop

If you notice basil or lemon balm dropping leaves from the bottom of the stem, it’s a cry for help. The plant is shedding leaves because it can’t support them. If it can’t support the leaves it has, it definitely can’t handle you taking the healthy ones from the top.

Frequency vs. Quantity: The Balancing Act

There is a debate in my head every winter: Is it better to take one big harvest once a month, or tiny harvests every few days?

Through trial and error in my apartment, I have found that frequency is better than quantity in winter, provided the quantity is tiny.

Taking one or two leaves of parsley every three days seems to shock the plant less than taking three whole stems once a month. It seems that constant, micro-pruning keeps the plant active without overwhelming it.

However, this requires discipline. You can’t get carried away. I literally count the leaves. If I’m making an omelet, I’ll take two chive blades. That’s it. It feels stingy, but it keeps the plant green.

The “Top-Down” Approach

In summer, I often cut deep into the plant to encourage bushiness. In winter, I stick to the very tips. I harvest the newest growth (which is usually the most tender anyway) and leave the older, lower leaves alone. The older leaves are the workhorses. They are tough, fully formed, and are doing the heavy lifting of photosynthesis. I leave them there to keep the engine running.

Specific Case Studies from My Apartment

Let’s look at how this plays out with specific plants I’ve grown on my windowsills.

The Basil Struggle

I treat my winter basil like it’s made of glass. I have found that basil is incredibly moody about winter drafts. Even if I don’t harvest, just the cold air from the glass can make it sulk.

In the winter months (November through February), I almost completely stop harvesting basil. I might pinch off a flower bud if it tries to bolt, but I leave the leaves alone. I look at it as a decorative houseplant during these months. By letting it rest completely, I usually manage to keep it alive until March, when the sun gets stronger and I can start snipping again.

The Parsley Workhorse

Parsley is the opposite. I have a pot of flat-leaf parsley that I harvested from all last winter. The key was patience. I noticed that after I cut a stem, it took about three weeks for a replacement stem to reach a usable size (compared to maybe one week in summer). So, I just adjusted my cooking. I used parsley less often, but I didn’t have to stop completely.

The Rosemary “Haircut”

My rosemary plant grows incredibly slowly indoors. In winter, I don’t cut whole branches. Instead, I just snip the top half-inch of the green, soft needles at the tips. This gives me that piney flavor for my roasted vegetables without cutting into the woody parts of the plant. Rosemary struggles to regrow from old wood in winter, so staying in the “green zone” is critical.

When to Stop Completely

There is a point where you simply have to accept that the season is over. If your plant looks scraggly, with long stretches of bare stem and only a few leaves at the top, stop harvesting.

At this point, harvesting is just cosmetic surgery that won’t work. The plant is likely “etiolated”—stretching for light. If you cut it now, you are just removing the only part of the plant that is successfully finding light.

I have killed many plants by trying to “prune them back to health” in January. It rarely works. If the plant looks sad, let it be sad. Keep it watered (but not too wet!), keep it in the best light you have, and wait. Often, these ugly duckling plants will explode with new growth as soon as the days get longer in spring.

How Weather Affects Your Decision

Even though we are gardening indoors, the weather outside matters. On cloudy, dark weeks where we don’t see the sun for days, I don’t harvest anything.

If we have a week of bright, crisp, sunny days, I know my plants are getting a little energy boost. That is when I might snip some herbs for dinner. I try to time my harvesting with the weather. It sounds a bit obsessive, but in a small apartment with limited windows, you have to take every advantage you can get.

For more insights on how environmental factors like light and temperature influence plant dormancy and growth cycles, you can look at resources from the University of Minnesota Extension, which explains the science behind plant energy needs during low-light months.

Conclusion

Can you harvest herbs in winter? Yes. Should you? It depends on how much you value the long-term life of the plant versus the flavor of tonight’s dinner.

My approach has shifted from trying to force summer yields out of winter plants to appreciating whatever small handful of leaves they are willing to give me. By respecting the plant’s slower pace and strictly limiting my harvest to that 10% range, I’ve managed to keep my indoor garden productive year-round.

It takes a bit of self-control to look at a basil plant and walk away without picking a leaf, but when spring comes around and that plant is healthy, strong, and ready to take off, you’ll be glad you gave it a rest.

Next Steps for You

Go check your indoor herbs right now. Look closely at the new growth—is it pale? Is it stalling? Based on what you see, decide which one plant in your collection needs a “Do Not Disturb” sign for the next month.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. If I stop harvesting, will my herbs get woody and bitter?

In winter, this is rarely a problem because growth is so slow. In summer, we harvest to prevent plants from bolting (flowering) and turning bitter. In winter, most herbs (except maybe cilantro) aren’t growing fast enough to bolt. They are just trying to stay alive. You don’t need to worry about them getting “too old” during these few cold months.

2. My basil is dropping leaves even though I’m not harvesting. What should I do?

If you aren’t harvesting and it’s still unhappy, it’s likely an environmental issue. The most common winter killer for basil is cold drafts or wet feet. Move it away from the cold glass of the window (even a few inches helps) and make sure you aren’t watering it as much as you did in summer. Winter plants drink much less water.

3. Can I harvest from a plant that I just brought inside from the garden?

I would wait. When you move a plant from outdoors to indoors, it goes through “transplant shock” due to the change in light and humidity. It needs time to acclimate. Give it at least 4 weeks of rest to settle into its new apartment home before you start snipping at it.

4. Is it better to harvest morning or night in winter?

The general rule of harvesting in the morning (when essential oils are highest) still applies in winter, but it matters less. Since the sun isn’t as intense, the oils don’t evaporate as quickly during the day. However, I still try to snip in the morning just out of habit. The most important thing is how much you take, not necessarily what time of day you take it.